Earlier this month the Japanese ambassador visited New Mexico. He was not in town to visit Carlsbad Caverns or to throw a pizza onto the roof of the Breaking Bad House. Unlike the usual tourists, he was in Santa Fe to discuss the newly announced Western States and Tribal Nations Energy Initiative roadmap for Rocky Mountain Gas. This roadmap spun out of a visit to Japan and Singapore earlier this year by several U.S. government officials, including the Governor of New Mexico. One of the core ideas in this roadmap is that New Mexico and other Western states could begin to sell natural gas to Asian countries. The Japanese ambassador was positive but noncommittal, saying that importing gas from New Mexico “is one of the options we will have on the table” as part of Japan’s tariff agreement with the Trump administration which requires that Japan spend $7 billion per year purchasing U.S. energy.

This bizarre situation raises some obvious questions. New Mexico is landlocked, so how are they planning to get gas to Japan? What coastal state will cooperate and why aren’t they involved in these discussions? Without an explicit deal with Japan and other Asian countries who would put up money to build export infrastructure? Will Japan continue to be interested if the next presidential administration scuttles the tariff deal? Most bafflingly, why is a governor that is committed to achieving net zero emissions negotiating with a foreign country to encourage fossil fuel expansion?

The New Natural Gas Export Paradigm

Grappling with these questions requires context both around New Mexico’s gas production and the broader global gas market. U.S. gas is not a monolith; local factors heavily influence the specific economics of each basin. New Mexico is the third largest gas producing state in the country, trailing Texas and Pennsylvania. It straddles two major production areas. Southeast New Mexico sits on the Permian Basin, the U.S.’s highest producing oilfield. Northwestern New Mexico sits on the San Juan Basin, which produces much less oil but is the country’s second largest gas field.

Interestingly, the San Juan and Permian Basin have some similar economic problems. Both basins have limited pipeline capacity to get gas from wells to markets. With more gas than ability to get gas to market, gas from these basins often sells for cheaper than other gas in the U.S. However, where they differ is in their geographic access. While the Permian has limited pipelines relative to its production, the major pipelines that do exist give ready access to bring gas from West Texas to the Gulf Coast. From there gas can be cooled down and compressed into liquid natural gas (LNG) where it is then exported to Europe and Asia. The San Juan and the other Rocky Mountain Basins are very far from the gulf coast and the Rocky Mountains have made development of pipelines to the West Coast difficult. In effect, this has turned the Rocky Mountain Gas reserves into a domestic resource, primarily used by nearby states to meet their own gas demand. However, the globe is in a moment of intense optimism about the prospects of U.S. gas exports which appears to be driving the reconsideration of building gas pipelines over the Rocky Mountains.

After the invasion of Ukraine, Europe lost access to much of the Russian gas that it relied on. Some of the unmet energy demand this created was resolved with domestic renewables, but it also pushed Europe towards more import of LNG from countries including the U.S. Coupled with this, Asia has seen a major increase in LNG demand first driven by Japan’s deemphasis of nuclear power in the wake of the Fukushima disaster and then as an alternative to coal for many developing Asian countries. This burgeoning demand has been encouraged by Japan which has leveraged its diplomatic influence to position LNG as a cleaner alternative to coal. That argument has continued despite academic research indicating that LNG, once its full life cycle emissions are accounted for, is not just a dirty power source but actually a dirtier power source than coal. Notably, Japanese energy and finance companies stand to profit tremendously from other Asian countries importing more LNG both due to their own export resale capabilities and their investment in US LNG infrastructure.

With all of this new potential global LNG demand, the U.S. has seen large interest in expanding LNG export capabilities. Several new LNG facilities in the gulf coast are currently being constructed and on the West Coast, Canada is also developing new LNG infrastructure. Despite optimism about potential demand, the financials of these facilities have been hotly debated with many fearing that a glut of LNG supply will outpace demand and crater the market. These concerns have led to some proposed facilities stalling due to a lack of investors. This debate has been elevated in recent weeks after Venture Global, a major LNG export company with facilities in Louisiana, was found in arbitration to owe over one billion dollars to BP for not meeting supply contracts.

New Mexico’s plan

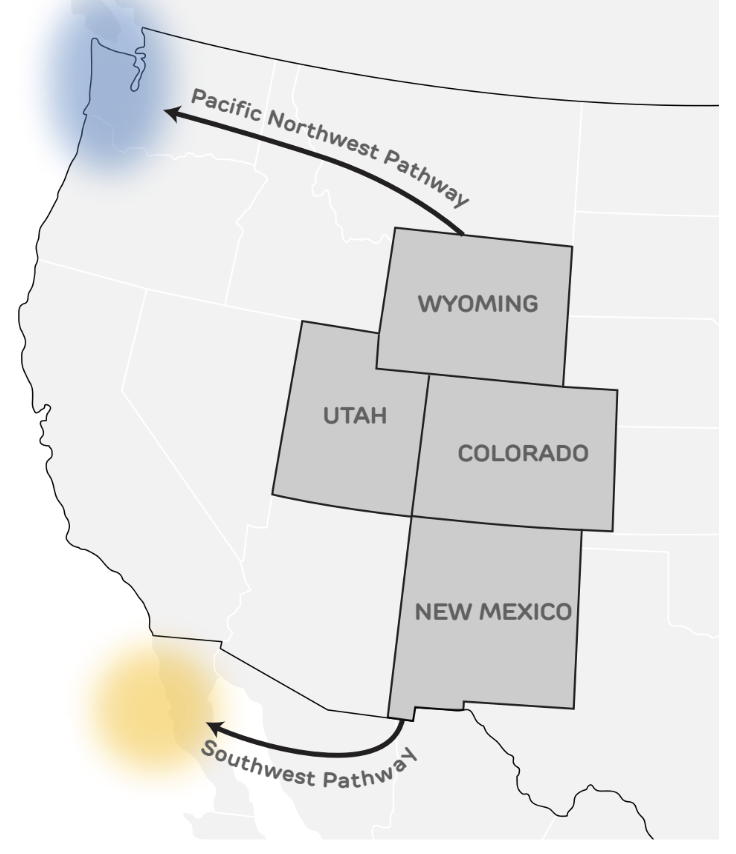

Against this backdrop, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, the Mexican state of Baja California, several Colorado counties and indigenous governments released their Rocky Mountain gas roadmap. The report paints a rosy picture of the prospects for exporting Rocky Mountain gas, arguing that pipelines can be constructed either south of the Rockies into Mexico to be exported from Baja California or through the Rockies to be used by the Pacific Northwest and potentially be exported from Oregon (who notably is not part of the publishing group). The report acknowledges that historically, West coast energy markets have not been strong enough to justify the exceptionally expensive investment in moving gas over the Rocky Mountains, but predicts that growing energy demand for data centers and onshoring of manufacturing will drive sufficient demand. While the massive infrastructure undertaking to build gas pipes over mountains may lead to higher gas prices than Permian gas exported from the gulf, the report argues that by avoiding the Panama canal to get gas to Asia, Rocky Mountain gas exported from the West Coast will get to Asia faster and more reliably.

Against this backdrop, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, the Mexican state of Baja California, several Colorado counties and indigenous governments released their Rocky Mountain gas roadmap. The report paints a rosy picture of the prospects for exporting Rocky Mountain gas, arguing that pipelines can be constructed either south of the Rockies into Mexico to be exported from Baja California or through the Rockies to be used by the Pacific Northwest and potentially be exported from Oregon (who notably is not part of the publishing group). The report acknowledges that historically, West coast energy markets have not been strong enough to justify the exceptionally expensive investment in moving gas over the Rocky Mountains, but predicts that growing energy demand for data centers and onshoring of manufacturing will drive sufficient demand. While the massive infrastructure undertaking to build gas pipes over mountains may lead to higher gas prices than Permian gas exported from the gulf, the report argues that by avoiding the Panama canal to get gas to Asia, Rocky Mountain gas exported from the West Coast will get to Asia faster and more reliably.

Hopes and Dreams

In many ways, the report is strange in the specificity of its predictions given the vagueness of its proposal. The roadmap proposes two different pipeline pathways. Both cross state boundaries and would require federal approval that does not currently exist. One terminates in facilities that do not exist in a state that has historically blocked permits. The other would require cooperation between the U.S. and Mexican governments even as Mexico is considering a bill to ban fracking. There are no proposed operators for the systems and the suggested banks financiers are purely hypothetical (and notably are Japanese and Korean banks). The proposed purchasers have no contracts and have not made any commitments to purchase Rocky Mountain Gas. The economics of the proposal rely heavily on predictions that data centers drive increases in gas consumption in the Western U.S. However, the Western Electricity Coordinating Council (WECC), which manages the grid for the Western US and Canada is projecting that new data center energy demand will be met with renewable energy while some gas-fired power plants are actually decommissioned (the report appears to misquote WECC, saying that they are projecting a 20% increase in gas demand when they actually predict a 20% increase in electricity demand most of which will be met with renewables). Even the assumption that Asian demand for LNG will continue to expand is fraught. Japan has been decreasing its use of LNG for years and in 2025, both India and China have seen declines in LNG imports. Despite these ambiguities, the report claims to have arrived at an estimate for how much Rocky Mountain Gas would cost for Asian markets.

Whatever Governor Grisham may say, the roadmap is not “jobs and real opportunities”. It’s guesswork. It’s an idea, cobbled together by government actors to capitalize on a trend without a clear path to be actualized. Even if all of the moving parts could be successfully coordinated to make the plan a reality, the notion that it would be a good idea is a fantasy driven by the most optimistic interpretation of every fact. The free market is far from efficient, but one might expect that if a plan like this really were as profitable as the government portrays, companies would be chomping at the bit to get involved.

Instead, the report discusses the creation of a “Multi-state quasi-public entity capitalized by producing states” to guarantee loans and front money. To be clear, Wisconsin governor Mark Gordon, who describes himself as a “a strong believer in free enterprise and capitalism” and who criticized the Biden administration for not sufficiently supporting energy independence, is saying that the financial prospects for Rocky Mountain gas are so bad that they need socialism to make it work. We are living in a bizarre moment where fealty to oil and gas production is so strong for some politicians that they would betray some of their core beliefs to advocate for socialism to funnel American natural resources to a foreign country rather than let the free market embrace renewables.

The myth of low carbon gas

The report also claims that the gas provided would be a “low carbon alternative” to the Permian Basin gas. Like the sudden interest in exporting gas, this is a clear effort to capitalize on current trends in the gas market. As renewables have hit their stride in the global energy market, many fossil fuel purchasers have begun to set emissions targets for the natural gas that they use. These purchaser requirements are virtually impossible to enforce in our globalized supply chain because gas from the same area is commingled before it goes to market, meaning “clean” gas is typically mixed with dirty gas (clean being relative since it’s all dirty). However, these requirements have still led to a burgeoning market for “differentiated” gas, meaning low emitting gas which can fetch a market premium. The report posits these Rocky mountain producer states as a potential source for differentiated gas. It highlights regulatory efforts in New Mexico and Colorado to restrict emissions. It also advertises the relative emissions of the New Mexico Permian to Texas’s side.

Conspicuously absent in the roadmap is an actual figure for Rocky Mountain emissions. Just last month, the governor of New Mexico was celebrating a report showing that the New Mexico side of the Permian basin has an emissions intensity of 1.2%. While lower than the 3.1% the report found in the Texas Permian, 1.2% is still extremely high emissions. The industry’s own self ascribed goal is .2%. At 6x times higher than industry goals, New Mexico’s emissions are not a “low carbon alternative”. The most comprehensive aerial assessment of U.S. emissions ever published (Sherwin et al 2024), which is even lauded by industry representatives, estimates the DJ Basin, one of Colorado’s oil fields, to have an emissions rate of 1.08%. That report found that across surveys New Mexico’s emissions intensity varied from 2.0% to 9.68%. With such high emissions, it’s not surprising that the roadmap focuses on the quality of regulations in the Rocky Mountain states rather than the outcome of those regulations. No matter how great the regulations sound, it is clear that they are not working which implicates any effort to portray the Rocky Mountains as a source of clean differentiated gas.

Unfortunately, this “roadmap” lacks substance, but it is not surprising that the Japanese ambassador is keen to encourage it. Without any risk or commitments, Japan has encouraged a group of landlocked states to propose a plan to sell them cheap gas and finance the massive infrastructure undertaking using Japanese banks. It is unlikely this proposal comes to fruition, but it is nothing but upside for Japan. The risks are borne by the U.S., and if they really follow through on public backing, by the U.S. taxpayer in particular. While the proposal is unlikely to come to fruition for the reasons outlined in this analysis, that does not mean the report itself is harmless. The U.S. should not be expanding fossil fuel production. Proposing new ways to export fossil fuels, especially while claiming that it can be “low carbon” legitimizes the continued growth of an industry that is directly at odds with global climate goals. This is especially disheartening from the New Mexican Governor who has publicly championed achieving net zero emissions by 2050. The state is already far from achieving that goal, and expanding the oil and gas industry will only exacerbate those shortcomings.