BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster on April 20, 2010, was the worst oil spill in human history. BP stopped the flow of leaking oil on July 15th and finally announced that the well was successfully plugged on September 19th. One poll found that 70% of Americans disapproved of BP’s response to the spill. Another poll found that 81% viewed BP negatively and 69% viewed the federal government’s response negatively.

Whether an oil spill is on land or in water, the public reacts negatively toward those responsible. The damage is obvious because it’s easily seen. They can see what needs to be cleaned up and where.

What if I told you that there are hundreds, even thousands of hydrocarbon spills into our air on a daily basis? You might not believe me because the spills— like germs and viruses— are invisible. But even though you can’t see them, you still breathe in the harmful compounds in these spills just like you breathe in germs and viruses.

Hydrocarbon gases — which include compounds like methane that wrecks our climate and benzene that wrecks our health — are invisible. These gases can only be seen with technology. And that is the only reason the industry has gotten away with claiming methane gas is clean energy for this long.

Satellites are limited in what they can see, but if they are in the right place and under the right conditions, satellites can show us a representation of these invisible spills. Thermographers using optical gas imaging cameras on the ground are also limited to what we can see from a public road in the small area it’s possible to cover in any given day or night. However, optical gas imaging cameras can see hydrocarbon gases at night, unlike satellites. We can show you a video recording of what we saw in real time. Even with hundreds of satellites and thousands of thermographers, we won’t be able to show you everything. It’s too much.

While oil spills on land and in water are difficult to clean up, you at least know where the clean up needs to happen. There is currently no way to clean up the spills happening everyday into our air.

There are many ways these spills happen but most of the time the hydrocarbons are intentionally dumped into our air not unintentionally leaked. It’s important to understand that only about 6% of the methane released by the oil and gas industry is unintentional. That means 94% is intentionally released or spilled into our air.

Let’s Take a Walk

I’m going to walk you through two days in the field with NHK Japan Public TV reporters. During that time we witnessed some massive intentional oil and gas spills. All were by Energy Transfer (ET), a midstream company owned by Kelsey Warren who lives in Dallas. ET was one of the biggest polluters I had seen until they bought West Texas Gas, another big midstream polluter. Now ET is, by far, the biggest polluter I see.

While we continue to document ET’s emissions, the company appears to have other priorities. It is currently suing Greenpeace over its involvement in the Dakota Access pipeline fight. There is a trial set for early next year in North Dakota and last October residents of the area were mailed what appeared to be a local newspaper with “articles decrying the Dakota Access protests and praising Energy Transfer.”

Energy Transfer’s track record is one of donating to politicians to make sure they continue business as usual. After ET made $2.4 billion off of the 2021 winter storm debacle here in Texas, Governor Abbott did not hold the company accountable and then received a million dollar donation from ET.

E&E reported recently that ET’s CEO Kelcey Warren was at an event with Governor Abbott where they said that the new Republican administration had promised to, “get rid of the EPA regulations that have tied the hands of the energy sector in the state of Texas.”Knowing that ET is looking forward to getting rid of oilfield regulations, let’s take a look at how they and the rest of the industry claims these regulations have tied their hands.

Energy Transfer Keystone Gas Plant: “We are purging the plant for start-up.”

We arrived at the Energy Transfer Keystone Gas Plant at 12:10 PM on October 20, 2024. We stopped near the flares because I found one of the three flares unlit or malfunctioning on two previous occasions, March 17, 2024, and during a huge upset/blowdown event on September 15, 2024.

The flare was indeed unlit with a big, dense plume of hydrocarbon gas emissions including methane and volatile organic compounds. There was a strong smell of hydrogen sulfide gas and we could hear an intermittent loud jet engine sound indicating the plant was having a blowdown.

The NHK crew filmed the unlit flare and did interviews which took a while. Then we moved to the front of the plant and at 2:00 PM we started recording video of emissions from horizontal separator tanks. That’s when the plant manager came out to speak with us. In the beginning he was polite.

He informed us that they were “purging the plant for start-up.” That means they were purging the air/oxygen out of the system by pushing gas through it. During a purge, the gas is sent to a flare stack, called a control, to combust it. I told the manager that their flare was unlit but he ignored that. Regulations say that plants “must be purged to control.” A flare is considered a control because it is supposed to combust the gas. But the flare at this plant was unlit so it was releasing the gas into our atmosphere.

He looked through the OGI camera to verify the emissions from the separator tanks and then radioed someone to come close a valve. Then he started getting angry which concerned the NHK crew so they decided to leave without looking at the rest of the plant.

I watched the TCEQ Air Emission Event Report Database for several weeks and that event was never reported. Carbon Mapper has recorded four plumes from this site with one plume stretching all the way into New Mexico.

Carbon Mapper detected this methane plume that reached all the way into New Mexico

From January 1, 2023, to December 15, 2024, I found six reported emission events for Keystone Gas Plant in the database. One event they took back and said it wasn’t really an event. Three were caused by freezing weather or electricity failure. Several of the events exceeded permit levels. None of the reported event dates matched the Carbon Mapper plume dates. None of the reports covered the September event or the purge I witnessed.

Energy Transfer Compressor Station 176

On October 21, 2024, the NHK crew asked to visit a compressor station they had visited on their own the day before and found that it was making a very loud noise. Their research team identified the site as having large plumes shown by satellites.

We arrived at the site at 4:00 PM and heard the loud jet engine sound indicating a blowdown was in progress.

A blowdown is the purposeful venting of natural gas to the atmosphere during well operations and/or during pipeline operations or maintenance to relieve pressure in the pipe. ~Energy Knowledgebase

The blowdown was ongoing when we arrived. We were at the site for at least 1.5 hours and the site was in continuous blowdown. The blowdown continued as we left and the NHK crew said it was making the same loud noise the day before. It just happened to be another ET site.

Without technology like an OGI camera, there is no way to know a blowdown is happening, how long it lasted, or how much gas was released. I checked the TCEQ database daily for several weeks and this blowdown was never reported.

This site has appeared on Carbon Mapper five times.

One of five methane plumes detected by Carbon Mapper

I searched the emissions database from January 1, 2023, to December 15, 2024 and I did not find a reported emission event for this site.

Energy Transfer Mims Compressor Station

After visiting another site and making a pit stop, NHK wanted to see a big flare in operation and there was a giant flare that could be seen from many miles away not far from the 176 Compressor Station.

We navigated to the flare and found yet another Energy Transfer site that was having a blowdown. We arrived at 7:40 PM. But unlike the two previous invisible releases, this one was easily visible because the blowdown gas was routed through the flare. Routing gas through a flare is better for the climate and for neighbors’ health than releasing it uncombusted to the atmosphere. The intent is to combust the gas. But in this case the flare was not combusting efficiently so there was a big cloud of methane and VOCs visible through the OGI camera.

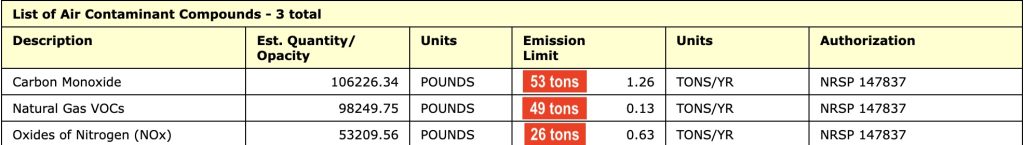

This very visible blowdown event (due to the large flare) was reported to the emission event database. The blowdown lasted for 295 hours and 3 minutes. Take a look at the second column and note the estimated quantity released. Then look in the fourth column and note what their permitted emission limit is for each compound. I converted the estimated pounds released to tons to easily note in red how far they exceeded their permit level with just this one release.

Image from report showing the site exceeded permit limits

From January 1, 2024, to December 15, 2024, I found eight reported emission events for this site and seven of those exceeded the permit limits.

This site is also a repeat offender on Carbon Mapper.

Methane plume detected by Carbon Mapper

None of the reported emission event dates matched any Carbon Mapper dates.

Where did the methane gas go? Energy Transfer Red Lake Gas Plant

Red Lake Gas Plant is about 200 yards from Mims Compressor Station. It was dark when we were there but I could barely see the shadows of equipment that looked like a gas processing plant. There were no lights on. Not one light. I looked at it through the camera and none of the equipment was hot.

This is from the Mims emission event report:

Image from report shows the plant was down due to electrical issues.

Gas from the Mims Compressor Station goes downstream to the Red Lake Gas Plant. There should be an emission event report in the data base for the Red Lake Gas Plant during the same timeframe. There is none.

We can estimate that the plant was down for about 295 hours and 3 minutes according to the Mims Compressor Station report. It is highly likely that every production site and compressor station that sends gas to the Red Lake Gas Plant would be over pressured because there was nowhere for the gas to go. Gas doesn’t stop coming up from the formation at production sites just because the plant stops operating. Every piece of equipment from the hole in the ground to the Red Lake plant would have been overpressured and releasing gas.

Where did the methane gas go?

The Spill Continues

Since the evidence shows that oil companies are not properly reporting methane emissions, it should come as no surprise that actual real world measurements of the methane emissions are much higher than the ones they report. Recently Gunnar Schade, associate professor at Texas A&M University summed up this slide from a presentation he attended. Notice how the measured methane emissions in the Permian are more than five times the numbers the industry reports to the EPA.

Graph showing that methane measurement are over 5 times higher than EPA estimates.

There is a massive methane spill happening in the Permian and the rest of the oil and gas fields in America and it has been going on for decades. It continues because, unlike the BP Horizon disaster, no one can see it.